From New Jersey Prison Break to Cuban Asylum

When the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that Assata Shakur had died in Havana at 78, the news lit up both U.S. and international media. The former Black Liberation Army operative, born Joanne Deborah Chesimard, had spent more than four decades behind the Iron Curtain after a dramatic 1979 jailbreak. Her story reads like a Cold‑War thriller: a 1973 shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike, a life sentence for the killing of State Trooper Werner Foerster, a courtroom full of medical evidence claiming she couldn’t have fired a weapon, and finally, a flight to Cuba under the protection of a communist ally.

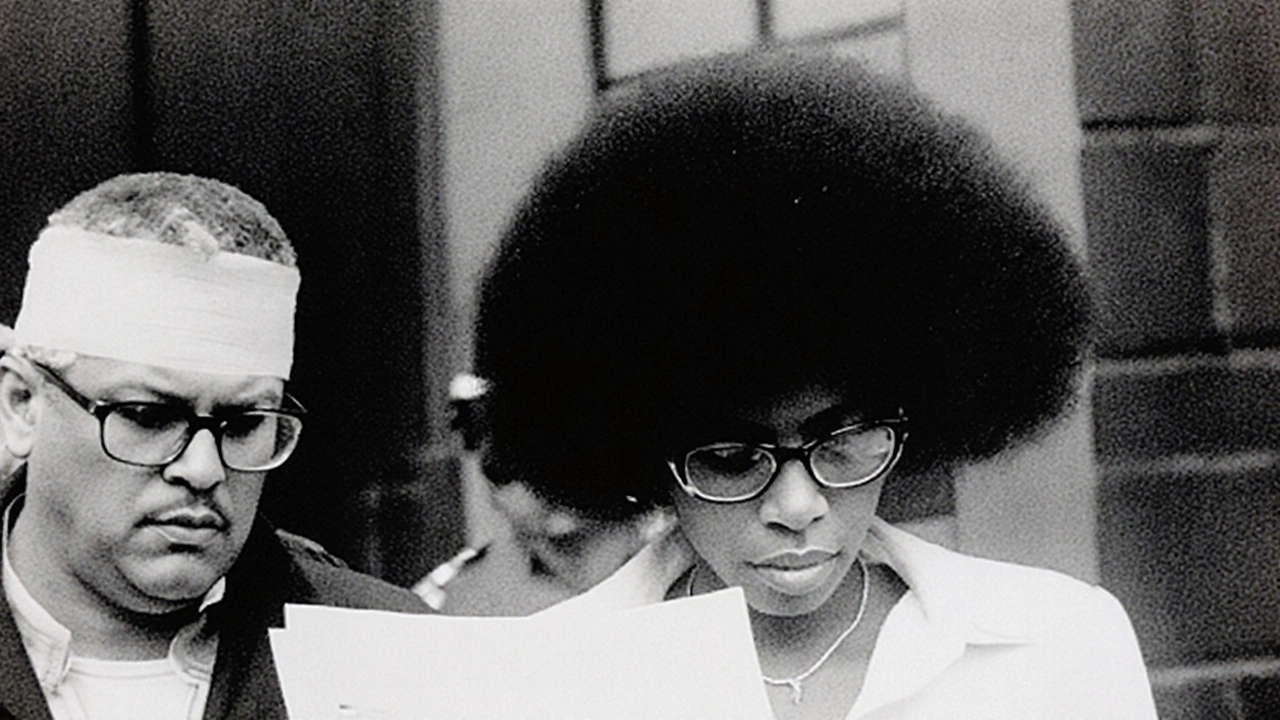

Born in 1947, Shakur became active in radical Black student movements during the late 1960s. By the early 1970s she had aligned herself with the Black Liberation Army (BLA), a clandestine group that embraced armed struggle against what it called a racist state. The May 1973 turnpike incident, in which two BLA members were killed and a state trooper died, thrust her into the national spotlight. Convicted in 1977 of murder, attempted murder, armed robbery and kidnapping, she was sentenced to life without parole and sent to the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women.

Inside the prison, Shakur’s supporters painted her as a political prisoner, while officials framed her as a dangerous militant. The story took a dramatic turn on November 2, 1979, when a coordinated raid involving BLA members and the May 19 Communist Organization allowed her to escape. She vanished from custody, resurfaced months later in Cuba, where Fidel Castro’s government granted her political asylum. The United States launched a relentless, decades‑long campaign to secure her extradition, but Havana consistently rebuffed each request, citing humanitarian and political grounds.

Legacy, Controversy and the End of an Era

Shakur’s name resurfaced in 2013 when the FBI placed her on its Most Wanted Terrorists list, making her the first woman ever to earn that designation. The move rekindled a polarizing debate: activists and scholars argued that her prosecution was a tool of state repression, while law‑enforcement officials maintained that she was a convicted cop killer who had evaded justice. Throughout her exile, she authored an autobiography, "Assata: An Autobiography," which became a staple in prison‑rights and Black‑liberation curricula, further cementing her status as a symbol of resistance for many.

Reaction to her death has been mixed. In Washington, a senior Department of Justice official called her a “dangerous extremist who escaped a rightful sentence,” while human‑rights groups issued statements mourning the loss of a “political dissident.” Cuban state media highlighted her contributions to the island’s revolutionary narrative, noting that she continued to work with local organizations on women’s empowerment until her health declined.

Legal experts note that her passing closes any realistic chance of a renewed extradition battle, but the broader implications of her case linger. The saga underscores how Cold‑War politics can entangle the criminal‑justice system, turning a murder conviction into an international diplomatic standoff. It also raises questions about the treatment of political activists in the U.S., the use of terrorism designations, and the lasting impact of 1970s radical movements on today’s protest culture.

As the world reflects on a life marked by prison walls, jungle refuges, and global headlines, one thing is clear: Assata Shakur’s story will continue to be dissected in classrooms, courtrooms, and activist circles for years to come. Her death does not erase the debates she sparked; it merely adds a final chapter to a narrative that has been as contentious as it has been compelling.